|

||||||||||||||

|

© 2001-2025 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Bumping Down Memory Lane: |

|

|

|

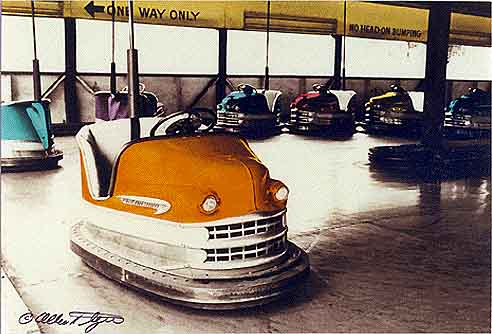

This year marks the seventieth anniversary of the classic American bumper car, the Lusse Auto-Skooter. To generations of sweaty ten-year-olds, the Auto-Skooter represented powered mobility in its simplest and most satisfying form. Here at last was a safe and sanctioned way to pay back pesky parents and playmates by ramming them repeatedly. And Auto-Skooters could take it. A 1940's ad proclaimed: "They [are] built to exacting LUSSE standards, which means built-in quality and stamina to spare." |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

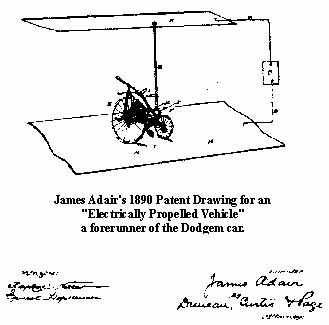

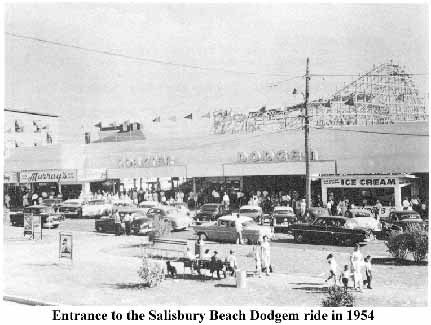

The Salisbury Beach Dodgem: By Betsy H. Woodman* As the 1920's opened in America, the automobile, so wholeheartedly adopted in the previous decade by the American people, was not only to come of age, but production was to saturate the market by 1929. No longer an experiment but a sophisticated assembly-line product available to the average American family, thanks in part to Henry Ford, over 5 million cars were manufactured in America in 1929, a record not to be equaled until 1949, another twenty years. The automobile with its benefits and its problems was here to stay and was rapidly changing the habits of America. Timing was ripe, and in a garage in Methuen, Massachusetts, the idea was conceived in 1920 for a car related amusement ride. Even Grandma and the kids were to have their turn at the wheel. Taken from the streets and corralled into a rink, miniature Dodgem automobiles were to give young and old alike a chance to have a legitimate date with a "smashing ride." Toward the end of the nineteenth century, during the height of the bicycle craze and when electric cars were being manufactured in America, on 25 February 1890 James Adair of New York was issued patent #421,887 for an "Electrically Propelled Vehicle."

He showed a lightweight tricycle located in a "rink" which was to be constructed with metal ceiling and floor surfaces that would conduct an electrical charge. When the proposed vehicle, via a vertical rod similar to a traveling trolley rod and via metal wheels or a metal disc, came in contact with the charged ceiling and the floor, the current would run an electromagnetic motor attached to the vehicle and thus propel it along. Envisioned by Mr. Adair as a method of transporting goods and people or as an "amusement device," a viable prototype was apparently never constructed. His 1890 patent, contained, however, the central idea that thirty years later would be realized in one of America's most successful amusement park rides, the Dodgem Car.

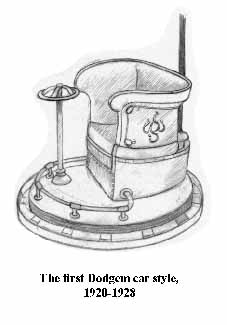

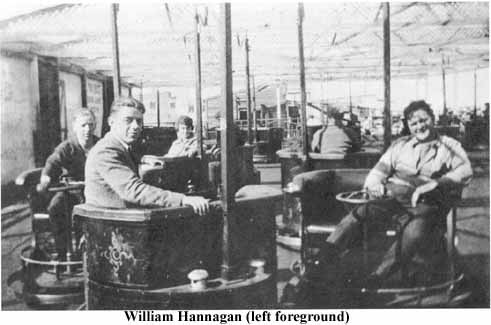

Between the Adair and early Dodgem patents, there was another closely related idea conceived by John J. Stock, who claimed never to have seen Adair's patent and who was issued patent # 1,339,299 on 24 May 1920. He depicted a large circular car that was to seat a number of people. The cars were to be operated in an enclosed space via electric motors with storage batteries, or like Adair's tricycle, via a conductor in a rink on a metal floor with a charged ceiling. Two cars, each seating ten people and weighing 3,000 pounds apiece, were actually built and given a trial run. called the “Glideabout", movement of the cars was sluggish due to their great weight, and the ride was deemed an immediate failure. Stock made a second attempt and filed for a patent on 5 November 1921, but patent # 1,669,104 was not issued to him until 8 May 1928. Here he depicted an electric-powered ride with smaller, four-occupant cars to be steered by the passengers. This ride did not prove to be a commercial success either, as the cars did not have the maneuverability of the smaller two-passenger cars, which were to prove so successful as manufactured by Dodgem, Lusse, and others. On the heels of Stock's idea, the first "Dodgem" patent (# 1,373,108) was filed on 7 December 1920 and issued on 29 March 1921 to Max and his son, Harold Stoehrer, of Methuen, Massachusetts. Also using electricity as the motive power, the patent called for self-propelled cars to be “equipped with novel instrumentalities to render their manipulation and control difficult and uncertain by the occupant-operator," in order to "provide an amusement device." As stated, the floor would act as “one electrode of the circuit over which the driving wheel of the motor travels, and through which the current is conducted to the motor, while the other electrode is an overhead conductor coextensive with the floor and traversed by a trolley connected with the motor." The Stoehrers envisioned their ride as one in which the operator's main attempt would be to "dodge" or avoid other moving cars and the bumper areas of the enclosed electrified arena. A series of four rollers, some fixed and others unguided, would help to assure that the cars would go off in unexpected directions, making the art of "dodging" a difficult one and assuring frequent collisions that would provide thrills for the car operator. As illustrated in the patent and as first built, the Stoehrer cars were round in plan and designed to seat two people. They had semicircular padded seats under which the motor was housed, and the horizontal steering wheel was mounted on a vertical post in front of the operator and passenger. A raised tubular metal railing around the crescent-shaped foot area gave minimal protection to the occupants' feet, and there were no seat belts to hold the driver or passenger in place. By today's standards, safety would have indeed been considered lax. A metal leaf spring surrounded the round platform base of the car so that when collisions occurred, the spring would receive the brunt of the impact. One of the first men to operate the ride was Wilbur R. Hannagan. Mr. Hannagan (who died in August 1984 at the age of eighty-three) provided the author with an account of Max Stoehrer's early "Dodgem experiment," which had a fifty-year lifespan at Salisbury Beach, Massachusetts: Max Stoehrer got the idea for the ride at a parking garage located on East Haverhill Street in Lawrence, near the Methuen line. It was a garage where people paid so much a month to store cars, and Stoehrer, and a half dozen or dozen people hung out there for an hour or an hour and a half in the evenings to pass the time. A kid with a stripped-down Ford would whiz around, turn circles, and he never did hit a post. This demonstration gave Stoehrer the idea for the ride because it was fascinating to watch and it looked like fun to do. Everybody was automobile crazy then, anyway. Stoebrer had a partner from Lowell, and one of their rides was the Whip. When Stoehrer got the idea to build the "Dodgem," his partner wouldn't let him try it out at Canobie Lake Park [Salem, New Hampshire], because he was afraid a new ride would be competitive with the Whip and would hurt business. Stoehrer needed capital to develop the ride, so he had to look elsewhere and that was toward Salisbury Beach. He figured that Ralph Pratt [1872-1921] 41 was one of the few amusement park promoter/investors in the area, so in the summer of 1920, Stoehrer took one homemade car to Salisbury Beach, and that was the first "Dodgem Car." That first car was built by Stoehrer in a bungalow located on Combination Street in Methuen. Stoehrer's son and I built the rest. The [Salisbury Beach] installation was at Driftway and Ocean Front North. Before we could build the cars we had to build a wooden platform for the floor, which we covered with tin and the ceiling was made out of chicken wire. Then we built the other nine cars right on the platform. The cars were round in design and were constructed with wood and covered with sheets of tin. There was a balance problem, and to keep the cars from tipping, the weight had to be centered in the main castor located on the bottom. Three smaller castor wheels were placed around the diameter of the base and these allowed the cars to move and they also acted as balance wheels. We painted all of the cars red, gave them a little fancy trim, and we were ready to open in the summer of 1920. Keeping the ride going was something! Between rides the cars had to be nailed back together. If someone kicked the next car he put a dent into it. The tin would get battered as the cars crashed into one another and pieces threatened to fall off. If someone drove a car into the wall or into a corner it was hard to restart it and Harold and I had to use a plank to push the cars back out onto the floor. We experimented that summer with all kinds of devices to absorb the impact: metal leaf springs on the sides, then rubber tires, and finally fenders. We also experimented with different motors. The mast or vertical post, which conducted the electricity, had a fuse, and when one car stopped, we had to run out and put in a new fuse. The gas pedal acted as a switch to turn on the motor and the cars stopped when the driver took his foot off the pedal. The cars drove "crazy." If the driver turned half way around he went backwards. Why? Because Stoehrer wanted the ride to be funny. Neither he nor Pratt could drive the things. Harold and I had to drive them, and they didn't come with power steering! I think this was the first ride that could be operated by the participants; at least it was the first one on the beach. To keep the riders in the cars, we tried to convince them that they would get electrocuted if they left the cars early. Some "Dodgem Car" safety device! When they asked why we didn't get shocked when we went out on the floor to push the car back or to change a fuse, we told them we wore porcelain insulators in our shoes and some were gullible enough to believe us! Sparks flew from the wheels and we both got shocked often, but we survived the first season. Popular? The ride was so popular that forty to fifty people would be lined up on a good day. The cars were always designed to hold two people, but since everybody always wanted to drive, we ended up with a lot of single riders per car so we had to jack the price up from 15 to 30 cents per passenger per ride. The ride didn't last long, maybe half a minute, and when it was busy, we were kept moving. Two of us ran the ride and at night or before the ride opened next day we nailed the cars back together, banged out the dents, and we had to tip each car over to grease the wheels and motor. At the end of the season, in the fall of 1920, Stoehrer sold the cars to the Topsfield Fair (Topsfield, Massachusetts). The ride was a great success and it made a lot of money. After the fair was over, all ten cars were put into a huge bonfire and burned! By then, I guess they'd been nailed together just about as often as they could be. At the end of that first season, Stoehrer was in debt for $8,000, but the ride was a success with the public, and Ralph Pratt came up with the financing. He bought a one-third interest for $33,000. In the spring of 1921 he bought 51% ownership and paid a balance of $120,000: the Stoehrer and Pratt Dodgem Corporation was formed. They couldn't decide on a name at first. It was to be "dodger" or "dodgem." They didn't want "bumper cars" because the idea was not to "bump" but to "dodge." Why? To save wear and tear on the cars. The first shop was opened in Merrimac, Massachusetts, and it was located there for only two or three years. The round-body style cars were made during these years. The sheet-metal bodies came precut, and they were assembled on wooden frames. The mechanical parts were installed, and in the last operation the cars were painted and then shipped out. It wasn't a very big operation, and by 1923 or 24 the factory was moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts. By then Stoehrer was out of the corporation, and Pratt had settled with him for a percent of the profits to be paid to him for eight or ten years. It was 8% for ten years or 10% for eight years. For the 1921 season, the first ride was rebuilt for Pratt in the same location at Salisbury Beach. The cars were built better but they were basically the same style and there were twenty cars built to replace the experimental ones of the previous year. A second ride was built at Lincoln Park [located between Fall River and New Bedford, Massachusetts] for Harold Stoehrer, and he called his ride the "Funny Ford." The third was built for White City Park in Worcester, Massachusetts, and that one was for Max Stoehrer. The first rides built and sold outside the corporation were for Rotherham and Bobb at Revere Beach, Revere, Massachusetts, and to an Englishman that I never did meet. The company would go in and put down the floor and the roof, which was chicken wire and was open to the weather. They charged $1,000 per car and the size of the floor depended on the number of cars ordered.

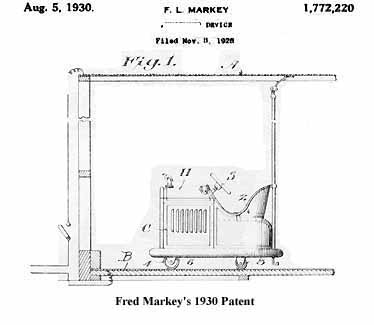

Launched in the fashion described by Wilbur Hannagan, Dodgem had other start-up troubles, mainly in the form of litigation. Parallel with Stock and his "Gadabout,” as the later version was called, the Stoehrers and Pratt built Dodgem rides during the opening years of the 192O’s. Dodgem "became a favored amusement attraction," and in 1923, it was announced that all the patent rights of J. J. Stock had been acquired by the Dodgem Corporation that all infringement proceedings had been discontinued, and that the Gadabout had been eliminated. It subsequently developed that Stock had an agreement with Lusse Brothers, a firm of machinists in Philadelphia, to produce his Gadabout cars. When there was no longer any demand for them, Lusse Brothers proceeded to develop a car of their own and named it the Skooter. This became a competitor of the Dodgem and patent litigation followed. In the meantime, both rides had become very popular with the public and numerous installations were made. "In the course of time, the claims of the two rival companies were adjusted and their rides have since been outstanding resort amusements." The second patent, # 1,467,959 held by "H. Stoehrer et. al.," was filed on 27 March 1920, (approximately nine months following the first patent filed on 7 December of the same year). Issued on 11 September 1923, this was an improvement of the first patent. Three unguided castors on swivel mounts and evenly spaced near the bottom perimeter of the platform (versus four in the first patent) were located not only to give the cars better balance but a more erratic performance. "The attempt of the occupant to steer the car by shifting the position of the traction unit (located off-center beneath the motor) at once suddenly imposes a new line of movement upon the swiveled castors which being unguided will not readily adjust themselves quickly to a new straight line of movement and are very likely to assume slightly different angles with reference to each other, resulting in erratic or promiscuous movement of the car as the occupant attempts to guide it." The traction unit and motor were also depicted in this later patent while the car design itself remained unchanged. The first two years of factory production took place in Merrimac, Massachusetts, under the direction of Mr. Carl Witham of Amesbury. Round-body style Dodgem cars were built during these years, and the company's first body modification seemed to be in regard to safety features. A low curved solid-metal front piece connecting with the body and the platform gave greater protection to the feet than did the open metal tubing of the first cars. A belt to hold people into their seats was at least shown in one photograph captioned 1922. However, as in automobiles, seat belts were not required until the late 1960’s. "In those days all the cars were hard hitters and when corning to a sudden halt you were more than likely to go flying across the floor, or lose a tooth or two on a handle bar or UNPADDED steering wheel. Lusse and Dodgem both used those old [wooden] Model-T type steering wheels which were inverted with the rim down and the HARD acorn nuts jutting up." And in the most terrifying of experiences… "My foreman told me on several occasions that people got knocked clear over the handle bar of the old cars, got up and dusted themselves off (while the others avoided them) and got back in and continued on." In 1923 the Dodgem factory was relocated to 68 Woodland Street in Lawrence, and the nearby offices were at 706 Bay State Building. With expanded fabrication capacity and demand increasing, a new and more sophisticated car called the "Dodgem Junior" was introduced. Dodgem was coming of age. The new car base was nearly oval in shape with a larger circumference at the end housing the motor over which one or two passengers were to sit. Patent # 1,652,840, filed on 26 October 1923 and granted on 13 December 1927 to Fred Stoehrer [assignor to Stoehrer and Pratt Dodgem Corporation], showed the new elongated design. A more stylishly curved metal back that tapered in and then flared out to meet the platform base and a bottom metal band, raised in front for foot protection, gave the body a continuous and graceful contour. With scroll-like decoration painted on the body and "Dodgem Junior" emblazoned on the front foot skirt, the car now had a more streamlined and sophisticated appearance. The steering post now slanted toward the passengers who fit into this car with much less room to spare than in the more bulky round-style cars. The patent noted that this was "a light practical car… particularly designed… in such a way as to avoid maintenance." The time had come for car design that did not require that dents be knocked out after each ride, or that the cars could be overturned daily for a grease job! Mechanical improvements brought Dodgem junior closer toward automobility. A "novel and practical slip clutch" was introduced. In the earlier cars, a switch or lever controlled by the car driver set the car in motion once the ride operator had closed the main circuit. In the newer model, the driver of the car had to be seated in order for his weight to close the circuit to the motor and he then had to throw the new slip clutch which connected the motor with the drive wheel, thus propelling the car. An active foot pedal meant that Dodgem handling more closely paralleled the driving of a real car, a correlation promoted in the advertising literature of 1926 and 1927: Each car seats two persons side by side, and is equipped with a steering wheel and starting pedal so that either or both riders can start, stop and steer the car about the floor. This is a feature that appeals to men, women and children of all classes, as it is a well-known fact that almost everybody is anxious to drive an automobile. For the experienced automobile driver, greater thrills are afforded, as they collide, sideswipe and chase one another around. Everyone delights in the Dodgem Junior combination of automobile driving features and dashing performance. Company brochures explained other improvements and spoke of the cost efficiency and durability. Beneath the headline which read, "No Fussy Mechanical Adjustments" and a depiction of the bottom of the car titled, "Bottom View Showing Simplicity and Rigid Construction," the following statements were made in the 1927 flier: "Long years of service is [sic] positively assured by Dodgem standardized quality. The driving mechanism, including a ¼ H.P. Westinghouse motor, is rigidly mounted in one unit under the seat away from all dirt and dust. A steel drive wheel and cut steel gear mounted in Timken bearings are supported by a heavy rigid frame requiring no fussy adjustments. The few mechanical parts are so easily understood that a mechanic is not needed. Any handy man that will keep the bearings lubricated is all that is necessary for continuous performance. All bearings are equipped with Alemite fittings and large grease reservoirs." Operating costs were stated to be "averaging about $3.50 per car per month." Labor was also said to be an economic benefit as a ticket seller and a floor operator, possibly two on busy days, were all the help needed to keep the ride going. The same brochure went on to rank the Dodgem as, "second only to the roller coasters that cost from four to five times more than the price of the Dodgem Junior ride complete." With a season's guarantee of parts and workmanship, what further inducement did the reader need to be convinced to buy a Dodgem Junior ride? Even buying terms were noted as "liberal." A 1922 ad (the last year of the round-body style) states that 800 cars were manufactured by the company during the year, but individual car prices were not given. In contrast, two years later, a 1924 brochure advertises Dodgem junior cars at $350 apiece. The price of a ten-car ride would then have amounted to $3,500 plus the cost of shipping and of a building. In their 1927 brochure the company reported: "Our terms are liberal, as we know that after the ride once starts operating, the receipts will take care of the payments due. There is hardly a single case where the ride has not paid for the cars and building above the operating expenses during the first year.” Letters of endorsement and a listing of the many ride locations were given to cancel out any final apprehensions the reader might harbor. Roy Huffman, Riverside Amusement Park in Indianapolis, Indiana, is quoted in the 1926 brochure: "I have about the oldest Dodgem Junior cars in existence, and have always been glad I purchased them. What I like about the Dodgem Junior is that it attracts the crowds and they like to watch it, and as we all know, no ordinary person can stand and watch someone else having a good time without trying it themselves, and once they try it, they are regular patrons for life." R. W. Adams of Long Beach, California, was more succinct, "The Dodgem Junior sure get the money. They simply can't resist it." The name and location of 136 U. S. parks and 14 foreign parks with Dodgem installations listed on a 1927 company brochure was meant to and did read like a Who's Who of amusement parks of the period, showing that Dodgem rides were being sold not only throughout the United States but in Canada, England, Cuba, Hungary, France, New Zealand, Denmark, Australia, and Hawaii as well. The Dodgem ride had not only come of age but had gone international in the same era that the Model-T Ford brought about economical automobility to thousands of working-class Americans. Nineteen twenty-seven was the last year of the Model-T, but the Model A would be in production by 1928, and it was in May of 1927 that Charles Lindberg made his famous solo crossing of the Atlantic from New York to Paris in the "Spirit of St. Louis." Nineteen twenties Dodgem brochures depicted buildings constructed specifically to house Dodgem rides. If details and size varied from park to park and region to region, the construction system seemed to be standardized. Buildings were rectangular, one story, and were constructed in post-and-beam fashion with a roof truss which allowed a clear span for the interior rink. The heavy posts appear to have been located at eight- or ten-foot intervals. Diagonal bracing or sometimes-decorative brackets gave the posts additional support at the eaves. A waist-high enclosure located around the floor of the metal-clad platform kept the cars inside the rink and gave onlookers a chance to watch the ride. In many examples the roof overhang also provided protection from the weather for observers. The roof truss systems varied. Gable, hipped, and curved rooflines were shown. The curved roofline with its rather elegant low-slung arch gave the most graceful appearance. The ceilings were covered with wire mesh through which the truss work could be seen. The size of the building depended on the number of cars to be purchased for the ride. Fifteen to twenty cars seemed to have been the most common numbers, although ten cars were probably the requisite for small-scale portable operations such as local carnivals. Larger installations might have been found in major amusement parks. If not incorporated in the front section of the building, the pay box or ticket booth was frequently a separate frame cubicle. Just large enough to house the ticket seller, it was generally located off to one side in front of the main building. When separate, this booth provided additional signage space for advertising the ride. In the pre-World War II era, the Dodgem Company did have a hand in building design as did their United States competitors, the Lusse Company. The Philadelphia Toboggan Company, major manufacturers of carousels and roller coasters also constructed buildings for their own rides as well as for others as attested by William Ford: Dodgem as well as Lusse and Philadelphia Toboggan all made portable and stationary Skooter/Dodgem buildings. The portables ranged from stark to elaborate, it all depended on how much the show moved and how much effort went into erecting the building and its trim. Lusse and Dodgem supplied drawings for buildings [permanent] that were quite elaborate. The companies acted as consultants when the building was being raised, and the decoration was part of the building. A lot of older parks still have a Skooter dodgem building left resembling what it once did in the thirties. Since Lusse and Dodgem were considered the "experts" (they were the only American ones anyway), the builders and owners pretty much stuck with what they proposed, since the addition of the neon /flash and other trim really only added on a small amount of cost to an already expensive building. When Dodgem, or Lusse for that matter, talked about "LIGHTWEIGHT" portable buildings, take it with a big grain of salt. Although I was lucky enough never to have to lug any portable building around, I did get rid of a partial building when the Lusse factory moved.... They had the posts stored in the basement and I had to move them out by myself I guess they weighed about 125 pounds apiece, being made out of long-leaf pine (solid), and there were many of these in a building.... The standard size buildings were 40' x 60' or 40' x 80' with many variations in between. Some buildings were converted for use to house the Dodgem ride and one was advertised in the company's 1927 brochure: The Dodgem Junior can be operated in any building having the required number of square feet for the number of cars to be used. This building [Central Park, Allentown, Pennsylvania] was formerly a restaurant, and was changed over for the operation of this ride at a small expense. Usually the installation of a steel floor, charged ceiling, and bumper are all that is necessary to convert any building for the operation of a Dodgem Ride. If buildings weren't as standardized as, for example, fast food chains of the recent era, neither was the signage. Done in a variety of fashions to suit the particular owner and his location within the park, some signs read, "Dodgem," others read "Dodg'em," and others were called the "Dashing Dodgem," and different lettering styles and signage techniques were used. Pulling in the customer was the job of both the sign and the open building, which allowed would-be customers to hang over the enclosure railing and cheer the drivers on their collision courses. One rink improvement brought out by the company during the decade of the twenties was a "Roller Bumper," first tried in 1927. "We are making up this attachment in 5 foot lengths so that it can be screwed or bolted on to [sic] your present bumper plank.... You will note that these rollers are practicable [sic], that they have been tried and have proven to add more pep and more business. In addition the cars cannot become fastened through friction any longer, which means that the riders keep going continuously." In seven years the company had indeed progressed from that 1920 opening season when the cars had to be pushed back onto the floor with a plank. When "art deco" or "art modern" styling, with its bold curves, streamlining, and other stylized details, became an established part of the architectural vocabulary of the 1920’s and 1930’s, amusement parks were not immune. One dynamic example of an art deco, Dodgem installation was the building in Atlantic City, New Jersey, located on Steeplechase Pier. Built in the 1930’s following a fire that destroyed much of the old pier in 1932, the building still exists. It is one of two that are alike. Architecturally their front flashboards are rather flamboyant, with ends that sweep up and curve around to the sides. Cosmic like projections in front have profiles that are enlivened by three-dimensional stars. In 1980 both of these buildings were painted bright yellow and blue, and the former Dodgem building had a newer bumper car ride with Italian-made cars. Surviving, but rapidly disappearing examples of such art deco amusement park architecture recall an era when many amusement parks were coming into their prime. The Dodgem ride as installed at Salisbury Beach in 1931 had a neon sign whose letters were rounded in art deco fashion, and this was replaced when the Dodgem and coaster signage was joined in a very handsome art deco scheme. Located on the south side of Broadway, midway between Ocean Front South and Railroad Avenue, a new roller coaster called the "Wildcat" was built by the Philadelphia Toboggan Company for the Dodgem Corporation in 1927, and in 1931 the company built a new Dodgem ride on the west side of the coaster. A disastrous fire destroyed this Dodgem building in September 1948 and also did extensive damage to the coaster. After both rides were rebuilt, they were joined or rejoined by a long flashboard. Painted white, this horizontal band above the entrances provided a surface for the red neon "Coaster" and "Dodgem" signs crafted in the severe lettering style of the deco period. This understated but sophisticated front for a decade or more gave a stretch of Salisbury's Broadway a handsomely coordinated art deco appearance. During the opening years of the 1920’s, Dodgem litigation issues were resolved, the factory was relocated, and the early experimental cars led to the successful Dodgem junior; the Stoehrer and Pratt Dodgem Corporation (which soon became the Dodgem Corporation) flourished. Max Stoehrer, by 1930 if not before, had retired to Florida, but not before Pratt brought Fred L. Markey (1893-1963), a Lawrence accountant, into the firm during these early organizational years. Markey quickly rose to the position of general manager, and from the point where the Stoehrers left off, he went on to improve the company patents and to promote the Dodgem ride. With the business structure and the major players in place and the Dodgem ride on its own "road to success," it was time for additional improvements, and they came in rapid succession before the decade was over. Three patents relating directly to the car design and mechanism were granted to Fred Markey as assignor to the Dodgem Corporation. The first, #1,772,220, filed on 8 November 1928, was granted 5 August 1930. For the first time, this patent showed a car style that approximated the look of a real automobile. The cause of this change was the relocation of the motor and drive mechanism:

"With the present arrangement, namely that of locating the combined driving and steering unit at the front of the car, the load or weight will be more equally distributed so that the car will pick up quicker in starting, thereby saving both motor and other equipment from unnecessary wear or strain and also permitting quicker manipulation of the car." Because the motor, however, was still mounted in a stationary position and the steering and traction units moved separately from the motor, the car was still designed to be driven in an erratic manner. For example, the patent states by making a half-turn of the driving wheel, the direction of the movement of the car may be completely reversed." Markey's second patent, #1,839,981, filed 18 December 1928 and granted 5 January 1932, showed a remarkable change in the way the car could be driven. The patent states, the present invention provides a combined driving and steering unit wherein the entire unit (including the motor) is rotatable with respect to the car for the purpose of controlling the direction of movement of the latter.... "The driver was hereby given control of the car so that when he turned the wheel left, the car went in that direction. It no longer went "funny" or in reverse at a half turn of the wheel. The third patent, #1,853,738, issue filed 25 January 1930 and granted 12 April 1932, was a further improvement of the steering wheel and drive mechanism. Along with the updated car body styling, the driving change was important to the continuing success of the Dodgem, as pointed out in Euclid Beach Park is Closed for the Season: From 1921 to 1929 the DODGEM used the most unwieldy of cars. They were rather cumbersome looking affairs, which turned left when the driver turned the steering wheel to the right, and went backwards when he attempted to go forward. Indeed everything was backward. These early cars were replaced by new front wheel drive machines in 1930. That summer, Euclid Beach Park [Cleveland, Ohio] featured sixty of the new models from the Dodgem Corporation... These cars reacted in the expected manner; that is, they went in the direction the drivers wished them to go. Perhaps you remember a voice instructing through a tinny [sic] public address system, "Traffic moves one way and one way only, no head on collisions please!" Nineteen twenty-nine was the first year that the Dodgem car resembled a miniature automobile, and in the decade before the war, production improvements continued to be made. The plain box front of the car was enlivened by a radiator grill and later rounded to coincide with the more streamlined look of automobile styles of the mid 1930’s. During these years the company began to experiment with the production of inventions that were not all related to Dodgem. Patent #1,888,005, filed 20 July 1931, was issued on 15 November 1932 to Fred Markey (of Lawrence) and Joseph R. Stanton (of Newburyport), assignors to Dodgem. Presented was a full-sized figure whose clothes hid a coiled spring body. Mounted on a circular rubber-bumpered disc that had wheels beneath, this movable target was to be placed on the floor of a Dodgem rink where it could be struck by the cars. When hit, the body was to “produce ludicrous gestures and also a noise making device will be operated to produce a shriek or groan or other sound.… Heretofore, the chief sport in the manipulation of the cars has been the feature of colliding with another car, and also causing ‘traffic jams’ which tax the skill of the operator to untangle. However, with the use of the novel shiftable target the sporting feature of the game is enhanced since it gives the driver of the vehicle an opportunity to strike the effigy or dummy with impunity and yet with safety.” Designed to automatically right itself after impact, the target was shown clad in a Keystone Cops outfit complete with bowler hat. How many of these were produced is not clear, but this seems not to have been a "Laurel & Hardy" success story in the amusement business.

A circus variant of the Dodgem ride was the next patent issued to Markey. Patent Precedent for the inclusion of a variety of animals in an amusement ride has an admirable history in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century carousels. Animal bumper-style cars were actually manufactured in Europe, but apparently without much success. Certainly Markey's proposed ride would have been costly to manufacture, and it is not certain that the company ever went into production. Having moved from Lawrence to Exeter, New Hampshire, Markey applied for his final patent with Harold Stoehrer of Manatee, Florida; they were both assignors to the Dodgem Corporation. Filed on 25 January 1934, and granted on 18 June 1935, patent #2,005,400 depicted a Dodgem motorcycle ride. A center island was to be placed in the rink to "assist in compelling one way traffic." Each cycle was to have a platform surrounded by a resilient bumper and was to operate in a manner similar to that of the Dodgem car. The ride was announced as "the NEW DODGEM CYCLE" in a 1933 flier that described it as "a full sized motorcycle redesigned and rebuilt for amusement park service, but retaining its motorcycle appearance.... The Dodgem Cycle cannot tip over and its speed is regulated for exhilarating thrills within safe limits.... One Dodgem Cycle can be added to your present Dodgem Ride to be used by a comedy cop for ballyhoo purposes." A prototype was to be shown at the National Amusement Parks convention at the Palmer House in Chicago, 1 to 3 November 1933. "Easy Rider" this was not to be, and like the circus idea, it never seemingly "got off the ground" or "onto the rink." Another idea spawned during the decade of the 1930’s was the "Dodgem Motor Boats." Like the Dodgem car, the boats were operator driven and seated two adults. As the Dodgem car had given many a first opportunity to "get behind the wheel of a car," so the boats gave many their first chance to operate a powerboat. Streamlined and slick in appearance, the powerboats were designed to give both driver and passenger the feeling of a luxury ride in a lake or lagoon. A brief eyewitness description of the boats constructed for this new ride was written in July 1932: "Visited Amesbury with Markey and looked over his new Dodgem boat which is a very nice looking job. It is considerably longer than the water skooter made by Lusse [Company] and built on a different principal. These are made all of wood. This, if it operates satisfactorily, should prove a very nice boat." Certainly the most elaborate early boat installation was done for the Chicago World's Fair in 1933. Another elaborate and memorable Dodgem boat installation was constructed six years later for the 1939 New York World's Fair. For this national event, the Dodgem Corporation teamed up with the Philadelphia Toboggan Company (PTC). Not only did they jointly operate a boat ride but also two Dodgem car rides. Both Dodgem and PTC were to have equal shares. Two buildings valued at $27,500 were to be put up by and mortgaged to the PTC, and Dodgem was to supply fifty cars valued at $20,000. For the boat ride, PTC was apparently responsible for the construction of a channel. How many boats were constructed or how profitable the three rides were is unclear. As to the popularity of boat rides, William Ford, who worked for Lusse Company after the boat craze had passed, reported: "They [boat rides] were very popular up to and after the second world war when operators wanted more space and had to get rid of the required lakes and artificial lagoons. Also, the price of gas went up as well as anti-pollution laws, which were forced on them [park owners] because of the filthy water that was in the lagoons. . ." Evidence suggests that Dodgem was out of the boat business by the time of the war. An expensive ride to install, outfit, and maintain, especially if a man-made lagoon was required, Dodgem motorboats were not destined to be the stellar performers that the cars proved to be. Elaborate boat rides would not return to the amusement park scene until Walt Disney and the development of theme parks in the late fifties and early sixties began to bring the likes of paddle wheelers and other large craft back to grand-scale manmade waterways. The Dodgem car was the bread and butter ride of the company, and it remained the staple in production. The elongated car body style of the late twenties and early thirties Dodgem models was maintained as the decade of the thirties continued, but changes were made that again related to automobile styling of the period. The boxy front end of the car was replaced with a more sleek "V" shape that was rounded in the front. This new overall shape became a standard car body base that was to be used from the prewar era to 1956. A variety of front grills were applied to ornament and update the models, but no radical change was to occur until 1957. On a limited basis, Dodgem cars were manufactured during the war, and by 1949, the year that Detroit had retooled and automobiles were again rolling off the assembly line in record numbers, the Dodgem company brochure could boast: Its design was conceived by an eminent industrial designer and is a definite factor in attracting patrons to the ride.... The MODERN STYLED BODY [is] designed in keeping with today's automobile trend. It is constructed of heavy gauge metal carefully reinforced, welded and securely fastened for safe, roomy, comfortable riding. [It is] finished in high luster Deluxe enamel in attractive colors. It will easily accommodate two adults or three children. The seats are meticulously upholstered in heavy, rich colorful material of long wearing qualities and carefully padded with FOAMEX, the sponge rubber padding now used in expensive automobiles, offering excellent cushioning and long life. Another aspect of the design pointed out, "THE MODERN EYE CATCHING RADIATOR GRILLE AND HOOD ORNAMENT is [sic] of highly polished cast aluminum which requires no plating and is of the corrosion resistance type." Details about mechanical parts were also depicted in a cut-away showing the motor, traction unit, and chain-driven steering mechanism. It was pointed out that "there are no gears in the DODGEM transmission. It incorporates a long proven conventional TWIN V BELT DRIVE which is efficient, noiseless and inexpensive to maintain." The one-half horsepower ball-bearing motor and heavy-duty single-drive wheel were also featured, along with other items in the script with a final note that the "CAR FLOOR is of kiln dried, spliced maple planking, 1-½ inch thick securely fastened and treated." No question, the cars were designed to withstand the impact of their collision course. In a 1956 brochure, the last year of the metal car body with its updated fifties' style grill, the portability of the ride was featured: "MORE CARNIVALS ARE USING DODGEM CARS THAN EVER BEFORE." A portable building was shown, and dimensions were given: "The Dodgem can be adapted to fit any park, large or small and can be successfully operated with any number of cars from lo to So. We will furnish standard permanent building plans without charge. An operating floor area 40’, x 50’ will accommodate 10 to 12 cars, 40’ x 100’ up to 30 cars." The claim was made that "more and more carnivals are buying Dodgem cars now that more practical portable buildings are available. Lighter and more durable construction and ease of handling have brought the cost of portable buildings to a point where it is now possible for smaller traveling shows to add this top money getter. Dodgem can help you get started with a worthwhile portable." Nineteen fifty-seven was an important year for the company. An updated car with a body constructed of fiberglass was introduced and billed as the "Sensational SPACE AGE DODGEM." The material was described in the new brochure as "tough, reinforced industrial Fiberglass (not plastic) that is superior to other materials for impact resistance, and -it won't dent or rust." The front, looking less like the hood of a car than former models, now had a streamlined rounded contour. Three strips of chrome pointing forward broke up the top surface, and two gracefully styled handles for getting into and out of the cars were attached on either side. Wrapping around the body was a second band of color that swept from the back of the car up toward the front and culminated on either side of the body in a fin design. This was finished off with chrome trim that emphasized the streamlined "futuristic" effect the company was trying to achieve. The fin design still, however, related the styling of the Dodgem to cars of the period, as did the two-color effect that was so popular in automobiles of the mid-fifties. The trolley poles for the first time boasted lights that were held in place by triangular struts located well above the head of a seated adult driver. These were no doubt intended to add to the effect of the "space" vehicle concept. In testimonial letters written to the company, after the 1957 season, the general manager of Playland Palace, Old Orchard Beach, reported on the performance of the new cars: "We found that the collision shock was much less than on the older style cars, due to the lighter weight, and that the handling and servicing was much easier." Another letter referred to the "flash" and "eye-catching" appeal of the new-styled cars and went on to say that the cars were easy to keep clean and new looking. All spoke of the great profitability of the ride as an attraction getter and also of the ease of maintenance. "The thing I like best about the Dodgem cars beside their beauty is the new motor which is made to stand low voltage. Fiberglass seemed to have eliminated the dent problem, and construction standards, as they had been from the early years, remained high to ensure a dependable, low-maintenance, and profitable product. Howard F. Parish began work for the Dodgem Corporation in 1949. He rose to the position of assistant foreman in the Lawrence factory, which by then had two locations. Opened in 1923, the smaller plant, a one-story frame structure, was located on Woodland Street. On Merrimack Street, Dodgem occupied the second floor of a five-story brick building formerly used as a textile mill. Offices were, by that time, no longer at the Bay State Building in Lawrence but at the IOKA Theater Building in Exeter, New Hampshire. During the summers, beginning in 1952, Parish managed both the Dodgem and coaster rides at Salisbury Beach for the Dodgem Corporation. Winters he returned to Lawrence to work at the factory until Dodgem was taken over by Herschell in 1961. After that date, Parish continued to manage the beach rides until the coaster was razed in the fall of 1974 and the Dodgem in 1975.

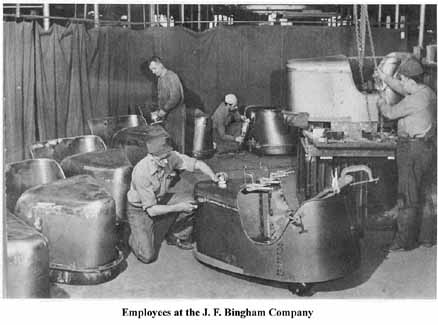

Howard Parish recalled the layout of the manufacturing process, the process itself, and maintenance aspects of the Dodgem ride at Salisbury Beach: At the Woodland Street factory, parts for the cars were made or pre-assembled. This operation was run by Ozzie Scheller, and he had five men on his crew, but we all pitched Each weighed over 100 pounds, and they came cut to size and shape with three cut-out holes. The large hole was for the traction unit, and there were two smaller holes for the steering column and for the trolley pole. The platforms were about two inches thick, and they were made of maple laminated in strips (butcher block fashion). These were made by the Lawrence Lumber Company and brought into the factory by truck. Linseed oil was put on both sides, they were stacked and allowed to cure for three or four weeks. While these were drying, other parts were made including the trolley poles and seat backs. Chain came in rolls, and this was cut to size and put together to run the drive unit. Other parts such as castings were cleaned up, sanded and pre-assembled here. I spent most of my time at the Merrimack Street factory where we had most of the second floor. Our job was to assemble the cars. Jack Carpilio with a three-man crew ran the front section, and with two men I ran the back section of the floor. Most of our parts came from the Woodland Street factory, but we had to order some supplies ourselves. We began our assembly with the platforms. On the bottom, across the mid-section of the platforms, we put on, with 5 inch steel pins, two 1-½ inch wide steel cross bars to hold the laminated wood platform together. Then we inserted a steel ring into the large cutout hole of the platform. This ring was 3 inches wide and 12 to 14 inches in diameter, and we bolted it to the floor with six 2-¼ -inch carriage bolts. This ring held the driving unit in place, and it contained three 1-½ inch diameter sealed bearings that allowed the traction wheel to rotate. After the ring was in place we installed the lower section of the driving unit. The traction wheel was about 4-½ inches in diameter, and the two back wheels were about 4 inches in diameter. These were mounted on stationary axle castors, and after all three wheels were installed, we could roll the heavy platforms around; this made it easier to assemble the rest of the car. The rubber bumpers were put on next. We first bolted steel bands to the edge of the platform. These had flanges on the top and bottom to hold the bumpers in place. Like the cross bars for the underside of the platforms, these bands were made up by the Bingham Company of Lawrence, and all of the bars and rims came predrilled. The rubber bumpers were especially made for the company and came from Ohio. They were all one piece, and we put them on with a tire tool. After the bumpers were on, we put in the rest of the driving unit which included a clutch, clutch band, a 6-inch shim for the belts, twin V-belts, the drive and steering chains and the motor. The motor was mounted on top of the drive unit, and these motors were specially made for Dodgem. They were always ½ horsepower and could be set to run clockwise or counterclockwise so that the cars would move in forward or reverse gear. In the early fifties we used Hozar-Cabot motors, in the late fifties Leelands [Leylands?], and the last were Brockmeyer motors from Ohio. Once the whole drive unit was completely installed, we put in the steering column and steering wheel. Our steering wheels were black, three-spoke, and they were not the same as automobile steering wheels. They were made especially for Dodgem, and after they were put on we were ready for the car bodies. The heavy gauge sheet metal bodies were also made by the Bingham Company. We bolted them on, did a lot of hand finishing work, and then trucked the cars to the Shawsheen Motor Company in Shawsheen where they were painted. Colors varied from year to year. Right after the war, in 1945 or 1946, there was a special allotment of 200 cars, and these were all maroon. In 1949 the colors were light blue, maroon, and dark and light green. In the early fifties yellow and white were first used, and at the end of the fifties the metal cars were two-toned: blue with light blue, salmon with black, black and white, yellow and black and red and black. When fiberglass bodies came in at the end (1959), these were already painted. They were made by a firm near Manchester, New Hampshire. Before the cars were shipped out, we put them up on horses in my department and installed the chromed aluminum trim. Although the trim varied, there was usually a hood ornament, strips on the sides of the cars, and a front grille. Finishing the seats was one of the last jobs, and, like the trim work, that was done in my department. We bought our foam padding in rolls in Lawrence from Dominic DiMaggio. The leather came in rolls from Boston, and it was black and red. The plywood seat backs were cut out at the Woodland Street plant, and after we covered the seats, we bolted them to the outside body edge. The very last item to be installed was the trolley pole, which came in two sections and was covered with a rubber sleeve. The lower pole made contact with the floor, and the upper pole had a trolley wipe or "shoe" at the end to run across the mesh ceiling. We tested the cars with a jump wire, and if they were to go any distance, they were shipped by closed freight car with their noses pointing up. Cleats held them in place. At first the freight cars came into the yard on Merrimack Street, but after they stopped, we had to haul the cars by truck to the railroad station at Parker and Merrimack Streets in Lawrence. A freight car could hold about seventy-five Dodgems, but we never filled up a car when I worked for the company. We shipped those that didn't have to go too far by truck. [For example], Mrs. Smith ran a big Dodgem ride at Revere Beach [Revere, Massachusetts], and we took her cars down by truck. The most cars we made in a single year after 1949 varied between thirty-five and fifty. We took used Dodgems in trade for new cars. [Of these], we rebuilt and sold a few to small operators, but most were scrapped. The Dodgem Company never bothered to design portable buildings, but they would send out a set of plans for permanent buildings and for buildings that were to be remodeled for Dodgem rides. Anyone who wanted a new building contracted themselves to have it built. From the factory we sent the insulators that were used to hold the mesh ceilings in place, the wire for lacing the ceilings, and we also gave out all of the specifications for materials. There was a schedule we followed at the factory during the year. We manufactured cars beginning in the fall and into the spring. The cars were made to order, and we finished our orders by the end of April, when customers wanted their shipment of new cars to start the season. In the summer we never worked on building new Dodgems. I was busy managing the Dodgem Ride at the [Salisbury] beach, and the factory crew did parts and repair work until fall. After the season closed at the beach, I was on the road doing repair work for the company during October and November. Most rides were seasonal, and they shut down like we did by the end of September. The Dodgem rinks were constructed with bumpers around the perimeter. Two parallel lines of 4 foot by 6 foot timbers surrounded the outer edge of the floor, which was covered with sections of 6 foot by 5 foot by ¼ inch thick steel plates bolted into the oak flooring. In between the two rows Of 4 by 6's was a 5 inch space. Heavy-duty coiled car springs were located at regular 2 foot intervals in the in-between space. These springs were bolted into the planking to act as shock absorbers when the Dodgem cars hit the sides (or rink bumpers). Steel plates overlapping the joints, where the 4 by 6's connected, were bolted into the timbers. In the course of a season the bolts holding these plates in place would work themselves loose; the constant impact of the 600 pound (plus passenger weight) moving Dodgems did a number on those joints! The loose steel plates had sharp edges, and they would cut the rubber bumpers of the cars. One of my jobs was to repair the fink bumpers by re-bolting the plates, and sometimes the car bumpers were so badly cut up that they had to be replaced. We kept both the Woodland and Merrimack Street factories going until just before the sale to Herschell (1961). About a year before the sale, everything was moved to Merrimack Street, and we continued this operation because we had to make up parts and keep the cars in repair. I was one of the last ones left who knew the operation. They couldn't get any skilled help to keep it going, and Fred Markey got sick, so Dodgem was sold, but we kept the ride going on the beach until 1975. 1 ran it for twenty-three years, from 1952 to 1975. We had forty-two cars in the beach ride. Thirty fiberglass cars were added after they came out [1959], and twelve metal cars were kept. Some of these were the maroon specials [of 1945 to 1946], and even when they became vintage, the cars were so well maintained that we had our fair share of riders. Every fall we trucked the cars back to the Lawrence Street factory for a complete overhaul. That was my job, and it took me and my crew of two men about two months to do the job. We also kept up the rink floor. After we closed down [in the fall], I had a heavy coat of car oil put on the floor to keep it from rusting. We didn't add sawdust because of the fire hazard. In the spring we put on a coat of lighter-weight range oil and used mops to mop up the worst of the slick. Then we put down paper to absorb the residue, and it took about a week for this to dry out before we could bring the cars back. We also kept the ceiling in good repair. Sometimes sections of a ceiling might need replacing, but this was uncommon. A new ceiling was nearly maintenance free, but they did wear, and between 1952 and 1975, while I ran the ride, we installed three ceilings. We used special order galvanized mesh. The holes were 1-½ inches apart, and the mesh came in rolls 5 feet by 150 feet. It had to be a fine gauge, or the wipers would break. After the old mesh was taken down, the new was stretched into place and then wirelaced together. Our ride was 40 feet by 100 feet, and to cover the ceiling we laced together eight sections running the length of the ceiling. It was some job, and it took four to five men two weeks of hard work to put in a new ceiling. We put 2 inch pipe around the edge of the ceiling. In between the pipe and mesh we used electrical insulators to which we laced the mesh every 3 to 4 inches. The insulators kept the electrical wire from touching the pipe. They were red-brown porcelain, and we bought them from Dyer Clark on Lowell Street in Lawrence. To keep the ride interesting we numbered the cars, but the kids got to know the faster cars, so toward the end we removed the numbers to keep the kids from fighting over their favorites. In 1955 we tried putting a series of rubber tires down the center of the rink floor to make the drivers go in one direction. It was safer for the little kids, but it took the fun out of the ride, and we were losing money, so we took the tires out after about a month. When we did this, we installed seat belts to make the ride safer. Seat belts were put into the cars by law in 1968 or 1969, but we were way ahead since we had had belts for over ten years There was a clock set by the operator to run the ride for 2 ½ or 2 ¾ minutes. When the juice was on, the ceiling was live, and the floor was the ground. If you touched the live ceiling, you got one heck of a jolt. If you needed to get to the ceiling for any reason when the electricity was on, you could get up on a ladder, and that was safe. Money collecting was a problem when I came to manage the ride. Three men with money machines on their belts were needed to collect and keep the ride going, and we had trouble with this system. We were losing money, so we bought Globe tickets, and a ticket booth was installed. This did away with collecting on the floor, and my wife, Yvonne, ran the ticket booth. When she began selling tickets, the price of the ride was 20 cents, and by the time the ride closed in 1975, the price had increased to 50 cents per person per ride. A pay-as-you-leave system was used so that riders could repeat and have their tickets punched without having to leave the ride. Mrs. Parish reported that "the busiest times for the ride were on Wednesday when it was 'Kiddies Day' at the beach, and on Friday and Saturday evenings. In good weather July was the busiest month during the short summer season. We opened on Easter Sunday and continued through Labor Day. In September we opened only on Sundays. We ran the Dodgem ride longer than some other rides on the beach because it was popular, and it was enclosed."

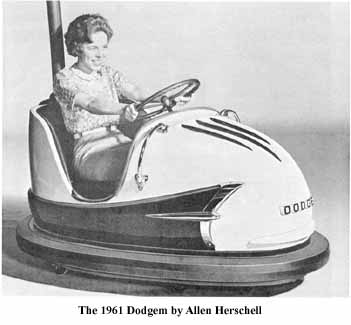

The 1957 Dodgem car was the last style to be brought out by the original Dodgem Corporation. In 1961 the company, still managed by Fred Markey, sold the Dodgem name and the business to the Allan Herschell Company, incorporated [a division of Lisky-Savory Corporation] of Buffalo, New York. Production was moved to the Buffalo plant, and the company continued to produce the 1957 style car for the following three years. In their promotional material, the Herschell Company called upon the reputation of their predecessor, referring to their product as, "the famous original Dodgem of Lawrence, Massachusetts." In the specifications, the size and weight of the cars were given. Width was 41 inches, length 67 inches, and the weight was 600 pounds per vehicle. Mechanical information showed that the internal workings followed the inherited Dodgem formula. Car colors, however, were updated. "New Fireflake molded in (the) body finish colors of Meteor Red" or "Chartreuse," a color of the fifties if ever there was one, was introduced. A new idea proposed that, "Bodies are easily changed so that, if desired, cars can be quickly updated when new body styles are introduced." Herschel hereby gave notice that they would attempt to solve one of the most perplexing problems of both the automobile and the Dodgem car builders: style. Trained by the automotive industry to expect yearly changes in car models, a fickle public demanded the newest in fashion. Yet because of the nature of the ride, the Dodgem car had to be well built to withstand the continuing shock of multiple collisions. Styles changed long before the cars wore out, and a demanding public looking for "the latest" was a constant pressure to the popularity of the Dodgem ride. Trade-ins had long been a policy of the original Dodgem company who rebuilt and resold used cars, but being able to bolt on a new car body, if economically feasible, would have made the Dodgem car even more competitive in the marketplace. Building plans that could "be readily followed by any carpenter using standardized and readily available materials" were advertised, and the Herschell Company also offered a 'Portable Model.' They also sold specialized items not readily available to set up the ride and these included: "coil springs for the bumper, center island accessories and insulators for solid metal or wire mesh ceilings." Either "110 or 220 Volt, single phase, alternating current" would run the ride. Run they did in both permanent and carnival operations, and by July 1969 the Herschell engineers had a new style of car on the drawing boards. This new car body was a design that returned to a more automobile like appearance than the 1957 model. The rounded front was replaced by one that had a long sleek box-like hood tapering toward the front and ending in a rectangle that once again imitated the grille of an automobile. Twin sealed-beam headlights were placed herein, and a single chrome strip highlighted the center of the hood, connecting it with the front grille. A thin chrome band encircled the car body near the base, also connecting with the grille. The two-color effect was eliminated but the "gleaming reinforced fiberglass, armor-strong, unbreakable body" remained the fabrication standard. "Smart... Fireflake Colors" with "thousands of tiny reflective particles deep into the colorful finish" were announced as "Golden Bronze and Candy Apple Red and Kelly Green," and all were to "glow with a deep inner radiance." Wider entryways into the cars and additional knee room meant that loading and unloading were to be faster, and for the first time a padded steering wheel was installed for safety. With "installation at Parks and Carnivals in twenty-six countries throughout the world," the 1920 Salisbury Beach experiment some forty years later was advertised as "The World Famous Dodgem" in company brochures. Newly designed cars would not, however, be incentive enough to bolster sales or keep aging Dodgem rides alive in the competitive marketplace, and having lost its edge, Dodgem production under Herschell declined rapidly. During the nine years that Allan Herschell Company owned Dodgem (1961-1970), only thirty-one of the new-style cars (designed in 1969) were manufactured before the Herschell Company was sold in its entirety in September 1970, to Chance Manufacturing Company, Incorporated, of Wichita, Kansas. After the sale Chance Manufacturing produced only two additional cars of the same design. These were the last Dodgem cars to be manufactured, and they were sold to the city of Green Bay, Wisconsin. Nearly ten years later, by 1980, the City of Green Bay had "sold all of their vehicles to persons unknown to us." With sales having dwindled, or having been allowed to dwindle, to only a few cars, the "smashing ride" was ingloriously over for Dodgem. From 1920 to 1970, over half a century, Dodgem grew to be a name synonymous with a well-built and successful repeat amusement park ride. Dodgem became a standard, as attested to by Geoff Weedon and Richard Ward in Fairground Art; they used the name Dodgem as a generic one to refer to all the bumper-car rides manufactured in Europe. During the early years of Dodgem production, a number of European companies took the idea and produced their own version. In America, the growth and development of the Lusse Corporation closely paralleled that of Dodgem, and Lusse is still making the "Skooter" today. In Europe, the company currently making the majority of bumper cars is Spaggiari of Italy, and many of their models are being imported into American parks. Ironically, this is even true at Salisbury Beach, where the Dodgem experiment began. The Mulcahy family Dodgem was torn down in 1975, and not a single car has been preserved on the beach to recall the Dodgem story. Roger Shaheen now has a bumper-car ride that features the Italian-made cars. When interviewed, those persons who have ridden the Dodgems recall the experience with nostalgia. For most it was a favorite amusement park ride one vividly remembered. Many had ridden as children and again as adults, and both driving and on looking were important features of the experience. Perhaps the most unique story was told by John White, curator of transportation of the Smithsonian Institution. When traveling through Eastern Russia in the summer Of 1979, at a stop in a fairly remote city he encountered an "amusement park." On a Dodgem type of ride the cars were moving at a slow speed. No bumping of any kind was allowed. If anyone dared bump, the ride was stopped. All of the cars moved in a line and when one revolution around the rink was completed the ride was over. The Ferris wheel was operated in similar fashion, with stops at every car to let people on and off. There were no free, nonstop revolutions of the wheel. The "thrills" or "fun" aspect Americans have come to expect in amusement park rides is obviously not one that is universally adopted. It might be said that Russian operating procedures will at least prolong the life of the machinery. Born in the shadow of the automobile, the Dodgem car ride was an invention that extended and popularized the concept of "automobility" both in America and in other countries. It is perhaps fitting that the ride was conceived in a garage and first manufactured in America, the country where an automobile culture developed most rapidly and is still, for better or worse, most pervasive. Unlike its grown-up big brother, the automobile, the Dodgem ride was happily limited to traffic jams of two- to three-minute duration. The electric motive power, in contrast to the gasoline engine, was not polluting, and a license to drive a Dodgem was not required. Dodgem cars were hardly avant-garde in design. Indeed, the company had a hard time keeping pace with the successive changes in American car body styles. Forced to build cars that were nearly indestructible by dint or "dent" of the very nature of the ride, the cars, if maintained (even minimally), did not wear out. Built-in obsolescence was not a part of the overall scheme, and as a consequence, a limited used Dodgem car market developed. A small number of trade-ins were rebuilt and sent out for extended use, and older-model cars were kept in running order and were frequently seen in combination with newer models. Competition with Lusse Corporation kept the Dodgem Company on its toes, and "foot pedal to the floor." Over a fifty-year period the Dodgem ride evolved from the first ten homemade Salisbury Beach cars to sleek, industrially designed fiberglass models. Started up in the era of Henry Ford's Model T, the Dodgems were, like Ford's "Tin Lizzie," designed to accommodate the populace at large. "Amusing the Million" for two or three minute intervals with teeth-shattering collisions--in between dodging--was the name of the game. A proven idea, Dodgem became a staple and set a standard for bumper cars in amusement parks worldwide. The Dodgem Corporation manufacturing operation could, in retrospect, hardly be considered as anything close to a major New England industry. During its life span under the control of the original company, from 1920 to 1961, it did, however, fit into that class of small specialty industries that have so long been a part of the spirit of "Yankee ingenuity." It was a successful scaled-down spin-off of the automobile idea, and it is interesting to note that Carl Witham, of a Merrimac and Ames bury car-body manufacturing family, was the key person responsible for bringing Dodgem from an experiment to a production item product which in short time was to find a world market. By the mid-to-late 1920’s, before the crash of 1929, Dodgem became a well-established flat ride in both the American and European amusement park vocabulary of "thrills and chills." This was indeed one of the great eras for Dodgem, as were the World Fairs in Chicago in 1933 and New York in 1939, when production exceeded by far the more modest thirty-five to fifty cars built during the postwar years. Ralph Pratt, company cofounder, never did live to see the international success of the experimental ride that he and Max Stoehrer initiated at Salisbury Beach with ten banged together homemade cars. That the corporation under the leadership of Fred Markey and others attempted, after Pratt's death, to patent, manufacture, and sell new ideas related to the Dodgem cars, namely the Dodgem Circus and Dodgem Cycle, is of interest in demonstrating the directed attempt of a small specialty company to diversify and survive during hard times. The Dodgem boats, at least for a time, seemed to have been a much more successful side endeavor of the company, and like the Dodgem cars they too were manufactured out of the ashes of an Amesbury car-body manufacturing industry that on a very decreased scale tooled down to make both Dodgem cars and boats. From what evidence survives, the marketing strategy of the Dodgem Corporation over the years was straightforward and predictable. In the enthusiastic period of the twenties, when the ride was new, catching hold and selling well, fairly sophisticated brochures were produced to show the product and to tout the successful entry of the company into the amusement park industry. Personal testimonials and lists of parks where Dodgem rides could be found were used to support the fast-growing popularity of Dodgem. And financial success appeared to be assured to any Dodgem car ride operator. After Ralph Pratt's untimely death at age fifty-two in 1924, Fred Markey became a major spokesman and salesman for Dodgem, ci steering" the firm through the early boom years before the crash of 1929. During this era, one major sales arena, which continued throughout the history of the company, was the National Association of Amusement Parks (NAAP), and later the International Association of Amusement Parks (IAAP) annual catalog and convention. For many years the old Hotel Sherman in Chicago was the site of the November convention, which by the early 1970’s had not only outgrown its quarters at the hotel but had begun to move to other United States cities such as Atlanta, New Orleans, Dallas, and Kansas City. The major trade-fair and meeting ground of the amusement park industry historically, as well as today, these cities are the places where new products are exhibited, and sales, if not clinched, are at least seriously entertained. Important contacts made at these fall meetings were no doubt instrumental in enabling the Dodgem Corporation to take their ride from Salisbury Beach to a far-flung marketplace in less than a decade, from 1920 to 1929. The New England division of NAAP also had annual meetings that were held in the spring. Serving as secretary-treasurer of this organization for many years, Fred Markey hereby kept current Dodgem contacts with New England park owners and operators. As is true in many businesses, and as a number of amusement park owners have attested, "in this business contacts are all important and being well known doesn't hurt." Time-worn and traditional, a network of contacts built up over the years helped keep Dodgem cars colliding in the rink, especially in the postwar years when production had dwindled from one known production high of 800 cars, advertised as the 1922 output, to a mere 50 cars per year by the decade of the fifties. With a proven product by the decade of the thirties, the Dodgem Company teamed up with an historic leader in the industry, the Philadelphia Toboggan Company, and with them, on at least one occasion if not more, managed to garner an important spot in the 1939 New York World's Fair for both Dodgem cars and boats. By the end of the decade, if not earlier, Dodgem had a full-time person, Cy D. Bond, heading up the sales staff. It is doubtful that he lasted with the company through the war years. It is interesting to note that earlier, Bertha Greenberg, who believed she was the only woman selling amusement rides during her time, began her career, "declaring she was successful," by selling Dodgems when they were first introduced in the 1920’s. By the postwar years the company had shrunk to a small production schedule, and it was never able to regain the momentum necessary to put it back, as it had been in earlier years, in the competitive international marketplace. The last glossy one-page flier to feature the Dodgem car was brought out by Allan Herschell to show off the company's new car design of 1969. Neither Herschell, whose success with Dodgem cars was quite limited, nor subsequently the Chance Manufacturing Company, made any major attempt after the early 1960’s to resuscitate Dodgem production or promotion. These sturdy machines, designed to survive in their own special brand of demolition derby, required the kind of handcrafting, especially in small-scale production that would certainly have made them prohibitively expensive in the marketplace. Having lost their fast-waning spot in the "greater bumper car rink" by the early 1970’s, Dodgem hit the bottom financial line with a crash that bumpers alone could no longer protect. Throughout the history of Dodgem, the original corporation never gave up its Salisbury Beach roots. During the slow times, and especially during the postwar years, continuing interests at the beach helped the firm maintain its solvency. Aside from the Dodgem ride, other rides, arcades, concessions, and a substantial roller coaster called the "Wildcat," built in 1927 by PTC and razed in 1976, were also operated by Dodgem (especially by Grace Pratt [1897-1963] and members of the Mulcahy family.) Such a cushion as the beach holdings provided allowed the firm to shrink back to a smaller and smaller scale of production. Weakened and crippled by internal problems such as lack of new funding, new management, and skilled labor, and caught up in the squeeze of increasing foreign competition, it was inevitable that the Dodgem name and manufacturing rights were sold in 1961. After the sale to Herschell, the interest of the original Dodgem Company in their own cars was only one of a custodial nature; they continued to maintain the Salisbury Beach Dodgem ride until it was razed in 1975. During their forty-one years in business (1920-1961), the original Dodgem Company did try to diversify into related rides, but they did not stray into the building construction industry. This they left to larger and better-equipped concerns such as PTC. The Dodgem car remained the mainstay of production, and the quality of both the car and the boats were high, perhaps too high; but that standard which ultimately, in part, led to the sale of the company, is perhaps the same aspect that made the "Dodgem" name synonymous with the more generic "bumper car." The Dodgem ride is now a ghost of the past, but its name is still remembered and connected with one of the longer running and most successful flat rides in the amusement park industry. The Dodgem ride gave onlookers, passengers, and drivers an acceptable and relatively safe outlet for mayhem in the arena of automobility. At least three generations have been brought up riding Dodgem cars, and it will be interesting to see how long the bumper-car ride, as manufactured by others, will continue to entice. Will miniaturized automobility as now seen in bumper cars, "themed" to appear in "Flintstone" garb and looking like moving rocks, or bumper cars made to imitate Model T's, extend the life span of this still-successful and durable flat ride? Perhaps the colors "Fireflake Candy Apple Red, Golden Bronze, and Kelly Green" have only temporarily faded from the amusement park scene in the arena of automobility where Dodgems once led the way. *Reprinted with permission from the Essex Institute, Salem MA

|

||||||||||||

| | Home | Wanted | For Sale | I.D. Your Lusse | I.D. Your Dodgem | Parts | Service | Bumper Rides | Legend/History | Disclaimer | Contact |